UNDERSTANDING DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER & CONFRONTING STIGMA

UNDERSTANDING DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER & CONFRONTING STIGMA

Have you ever arrived at your destination and realized you don’t remember the drive? Or gotten up in the middle of the night and had no memory of doing so? These experiences are surprisingly common and often go unnoticed. They are examples of dissociation—a psychological phenomenon where certain information fails to integrate with other aspects of awareness as it typically would. Dissociation exists on a spectrum, ranging from mild, everyday occurrences to severe and clinically significant disruptions. The most extreme form involves alterations in memory and identity, as seen in Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). Formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder. DID is described as “one of the most controversial diagnoses in mental health” (Arbour, vii). Despite the stigma surrounding it, DID is widely understood by clinicians as a complex coping mechanism developed in response to severe, often early-life trauma. The persistent misunderstanding and controversy surrounding the disorder are, in large part, perpetuated by misleading portrayals in the media.

To understand it all, you must first understand DID as a whole. This disorder, as previously stated, is developed as a coping mechanism to heal from past abuse. Biologically speaking, individuals with DID have their “psychic material remain conscious, merely pushing it to the back of their mind, leaving it available to directly interact with the external world, therefore explaining why DID patients’ alters, or self-states, can be coherent and organized” (Arbour, p. 10). With that being said, we turn to the actual self-states. Each patient with DID has different self-states, each serving its own purpose or reasoning tied to their past trauma. Two prime examples of these self-states are the host state and the persecutor state. The host state is typically the one who initially presents for treatment, as they tend to have executive control over the body. On the other hand, the persecutor state “views themselves as the enemy of the host state, often being the alter responsible for acts of self-mutilation, some of these abuses being recognizable as things that the original abuser would do” (Arbour, p. 12). Though DID can be seen as a remarkable coping mechanism, it is also important to recognize that living with it can be extremely difficult. Patients with DID are continuously working to heal from trauma that most people could not even bear to hear about.

In order to help everyone affected by this stigma, we have to address the leading issue in the cause of this stigma and that is the largest one of all. The media! The mainstream media is very well known for constantly spreading false information about anyone and everything; this is showcased in many different ways:

The book Sybil, later adapted into a film, tells the story of a woman named Sybil (Shirley) who suffered from Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), reportedly possessing 16 distinct personalities. This narrative of helplessness and eventual resilience became a bestseller and initially served as a source of inspiration for individuals with DID, helping them find the courage to speak openly about a diagnosis that was, at the time, considered rare. However, controversy emerged when it was later revealed that Sybil, with the encouragement of her therapist, had fabricated several of her self-states to avoid appearing disappointing. This revelation led to growing skepticism about the disorder and contributed significantly to the stigma that still surrounds DID today.

Although Sybil played a significant role in shaping public perception, the film that added the most fuel to the fire of stigma surrounding Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is the 2016 movie Split. The film features a character named Kevin Wendell Crumb, who lives with 23 different alters and is portrayed as dangerously unstable and violent. In the movie, Kevin murders three women and is even given an alter named “The Beast,” which grants him animalistic and inhuman traits. As one critic put it, “This movie has demonized people who aren’t any more inherently violent than the normal person” (Newberry, p. 1), creating unnecessary stress for individuals already coping with the challenges of DID. Similarly, Barach noted that based on his review of the film, it “will not help society better understand DID. It will only add to the stigma of mental illness in our society” (Healthline).

This raises an important question: why does the media continue to portray DID in this harmful way—and why do audiences keep watching? The answer is twofold. Media production is driven by profit, with little concern for the harm caused, while audiences are often drawn in by sensationalized portrayals. However, if the media chose to use its influence responsibly and produced a film that accurately and compassionately depicted the realities of DID, it could help dismantle the very stigma it helped create. In such a scenario, everyone benefits: the media still earns profit, and society gains greater understanding and empathy for those living with the disorder. While the media plays a pivotal role in shaping public perception, it is not the only contributing factor to the ongoing stigma, and other causes must also be addressed.

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a profoundly distressing condition that can become extremely difficult to manage, sometimes leading individuals to turn to substance use or even, in severe cases, suicide. One might assume that the United States’ mental health system would offer effective support; however, this is often not the case for those with DID. Patients are frequently misdiagnosed and may spend over six years within the mental health system before receiving an accurate diagnosis. This delay is particularly troubling given the modern tools available that could significantly expedite the diagnostic process.

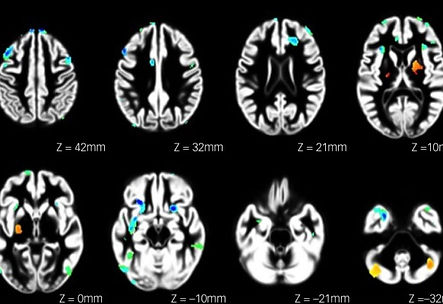

One essential yet underutilized resource is research conducted by various institutions. A particularly notable study was published by The British Journal of Psychiatry (BJPsych), which employed data-driven methodologies and structural brain imaging to identify potential biomarkers associated with DID. The study concluded that neuroimaging biomarkers could indeed aid in the identification and diagnosis of DID, offering a new and promising avenue for improving diagnostic accuracy. This innovative approach has the potential to dramatically reduce the time patients spend waiting for a diagnosis and, ultimately, to improve the quality of care they receive.

“DID and dissociative disorders, in general, continue to be the least explained and the most misunderstood of all psychological disorders within the NHS social care sector. It appears that little or no thorough education is provided to those studying to become health professionals” (Rethink Mental Illness, p. 5). The way mental health professionals treat individuals with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) remains a significant issue. To address this ongoing problem, it is essential that we take full advantage of the resources currently available. Specialized training programs focused specifically on DID, such as those offered by the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) and Harvard Medical School, are accessible to professionals. These are just two of many programs designed to improve understanding and care. The high rates of misdiagnosis and the excessive time patients spend in the system underscore the urgent need for such education. It is imperative that mental health professionals take initiative to pursue these opportunities as a necessary step toward improving outcomes for DID patients. Moreover, stigma does not discriminate—it affects not only the general public but also healthcare providers. “Some professionals may not recognize DID as real and, therefore, do not diagnose it. Then there are those who believe DID exists, but only in the exaggerated way that DID is often portrayed in the media” (Rethink Mental Illness, p. 3). This highlights yet again the harmful influence of media misrepresentation, which not only affects patients but also their friends, families, and even their doctors. Mental health professionals have a duty to support individuals who cannot advocate for themselves. A diagnosis like DID is life-altering and must be approached with care, objectivity, and seriousness—especially by those in positions of clinical authority. While it is understandable that everyone has personal beliefs and biases, those working in mental health must learn to set those aside to ensure diagnosis and treatment remain fair, evidence-based, and timely.

Although the stigma surrounding Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a significant concern, it is important to recognize that this issue reflects a much broader problem. Stigma is not limited to DID; it also affects many other mental health disorders, impacting hundreds of thousands of individuals worldwide.

In September 2022, a study conducted by Cambridge University aimed to determine which among five mental health disorders was most heavily stigmatized. The disorders examined included Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Depression, Schizophrenia, and Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD). The results revealed that Schizophrenia and APD were the most stigmatized (Cambridge Press, Results). It is worth noting that the least stigmatized disorders in the study—OCD, GAD, and Depression—are also among the most common and widely recognized mental health conditions. In contrast, the most stigmatized—APD and Schizophrenia—are less prevalent and often misunderstood. This comparison supports the idea that much of the stigma surrounding mental illness stems from a lack of public knowledge. As Health Direct explains, “stigma arises from lack of understanding of mental illness (ignorance and misinformation),” reinforcing the notion that education and awareness are key to reducing stigma.

Lack of knowledge is a problem that can be addressed with time, effort, and the right use of available resources. Accurate information about mental health disorders is widely accessible online. However, for individuals who already hold stigmatized views, access to information is not always enough. Many people engage in confirmation bias—seeking out information that supports their existing beliefs while ignoring evidence that contradicts them. As a result, those who harbor stigma are unlikely to seek or accept information that challenges their views or promotes understanding of disorders such as DID, APD, or schizophrenia. Compounding this issue is the role of mainstream media, which often prioritizes sensationalism over accuracy. Instead of highlighting research-based, factual representations of mental illness, media platforms frequently perpetuate harmful stereotypes. This is the core of the problem. To combat stigma effectively, we must take action and use the media as a force for good. By promoting accurate, empathetic portrayals of mental health conditions, the media can become a powerful tool for education and change.

The consequences of negative media portrayals for individuals with mental illness are profound. These portrayals can damage self-esteem, discourage help-seeking behaviors, reduce medication adherence, and hinder overall recovery. As noted in CNS Drugs, “Mental health advocates blame the media for promoting stigma and discrimination toward people with mental illness” (Abstract). In an era where change happens rapidly and access to information is unprecedented, it should not be so difficult to treat individuals with mental health conditions with compassion and respect. Those living with mental illness deserve peace and the freedom to exist without judgment. We must do better. Using the media to disseminate accurate, research-based information about DID—and all other stigmatized disorders—can benefit everyone. The media can continue to generate revenue, while also fostering greater public understanding and reducing stigma. On the clinical side, psychiatrists must approach diagnosis and treatment without personal bias. With countless available resources, including specialized workshops offered by organizations such as the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) and Harvard Medical School, mental health professionals are well-equipped to provide informed and compassionate care. Additionally, advances in diagnostic techniques provide even more tools to support accurate assessments. Together, these efforts—from both media and mental health professionals—can significantly reduce the stigma surrounding DID and mental illness as a whole. The ultimate goal is simple: to create a world where those with mental health conditions can live in peace.

In conclusion, stigma should not continue to surround Dissociative Identity Disorder or the many other mental health conditions impacted by public misunderstanding. We have both the knowledge and the resources necessary to drive meaningful change—and the media has the power to be a catalyst for that change. By choosing to promote accurate, compassionate portrayals of mental illness, we can bring justice to those who suffer, peace to their lives, and progress to society as a whole.

The images shown here depict the brain scans from the study published by BJPsych. The areas associated with DID are highlighted. Highlights being scattered in between white and grey brain matter.